After working for several years as a travel consultant with ETG, Lucy Reeve chose an admirable new path. Combining her love of travel, desire to work in the humanitarian sector and seriously impressive knack for languages, she joined the Operations Unit at international demining organisation, the HALO Trust. Since qualifying in 2017, she has travelled to Cambodia, Afghanistan, Somaliland and Georgia (to name just a few) clearing explosive remnants of war. Here, she shares an insightful article on her experience so far.

Conflict always leaves scars; some are physical and some intangible. Explosive remnants of war (ERW), in particular landmines, embody both the physical and intangible legacy that conflict imposes upon people – ruined buildings and landscapes, destroyed livelihoods, fear that every time your loved ones go outside they might step on a landmine and lose their legs…

People flee their homelands during war in search of safety, but when the fighting ends, all they want is to return home to normality. Tragically, displaced people often return to find that their land is unsafe – houses, roads, fields, schools, irrigation channels and the like are often contaminated with landmines and other explosive remnants of war such as unexploded ordnance (UXO). Peoples’ lives are brought to an abrupt halt when they are unable to farm their land, unable to gather firewood, unable to travel safely to schools, health clinics and markets for fear of injury or death caused by landmines. Poverty and desperation compel people to take unimaginable risks by working on dangerous land, simply to provide for their families. Landmines are indiscriminate – they do not differentiate between a civilian and a soldier and so everyone is a potential victim (nearly half of all civilian casualties are children). Try to imagine the bitter injustice of your life being ruined by the remnants of a war that has already ended. These victims want their lives back; they deserve their lives back.

Lucy with minefield managers in Samangan, Afghaistan

The HALO Trust saves lives and restores communities through humanitarian mine clearance and other activities such as unexploded ammunition disposal and weapons security. The challenges faced by ERW-impacted communities are ever-evolving, and HALO leads the effort to innovate and adapt so that more communities recovering from the scourge of war can be helped. HALO embeds in impacted communities and empowers local people to clear their own land of hazards by providing training and employment. Moreover, close cooperation with governments and development partners to make people and places safe ensures communities have the best chance to get back on their feet after conflict.

My story with HALO began after finishing my masters degree in conflict studies and whilst searching for a career in the humanitarian sector. I was lucky enough to travel widely in my twenties, during which time I visited countries where my life of relative privilege crashed headfirst into the poverty and suffering of people who had experienced conflict; I believe my profound desire to help victims of conflict was compounded during those moments of extraordinary disparity. One day, a friend told me about HALO’s work and suggested I apply. After passing the staff selection process, I embarked on HALO’s six-month training programme to become a member of the international operations team. The training covered topics such as mine clearance techniques, emergency medical treatment, battle area clearance, mapping and survey skills, international mine action treaties, basic account keeping, minefield management, working with explosives, land rover maintenance, socio-economic data collection, programme logistics and much more. I am currently serving in my first posting with HALO in Kabul, Afghanistan, and so far, it has been a challenging yet extremely rewarding experience.

However, mine clearance is not really my story to tell; rather it is the stories of the thousands of people who have benefitted from HALO’s work around the world that matter the most. In a manner far too brief to pay justice to any of these magnificent people, it’s my privilege to share a snapshot of the lives of the Cambodians, Somalilanders, Georgians, Abkhazians and Afghans who have guided my first steps in the mine action world so far.

Lucy and a friend during EOD training, Cambodia

Cambodia

After decades of conflict, Cambodia is one of the most mine-impacted countries in the world. On top of a quarter of the population killed and precious cultural relics destroyed, a particularly tragic legacy from the conflict is the K5 – a dense minefield along the border with Thailand laid by conscripts of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea to keep out the recently-expelled Khmer Rouge. The country is also awash with UXO, which continue to devastate families through injury and death and hinder socio-economic development. More than 80% of Cambodia’s population live in rural areas and rely on agricultural activities as their main source of income. As the economy continues to recover after the war, people are increasingly using mechanised farming assets to plough land for agricultural use. The use of heavier machinery that can cultivate deeper than traditional animal-drawn carts increases the risk of setting off mines. Moreover, people returning home after conflict are finding that their land is no longer safe due to the presence of mines and UXO.

Checking ground cleared by a deminer with a metal detector, Cambodia

I had been lucky enough to visit Cambodia twice before I went with HALO, and what a privilege it was to be reminded of the spirit and resilience of the Khmer people. HALO Cambodia has conducted clearance in parts of the country that tourists might be familiar with (the Angkor Temple Park for example), but also in places that are seldom visited by tourists – remote villages, border-crossing market towns and endless emerald-coloured farm lands. Many inhabitants of these areas suffer due to the presence of mines having once been refugees; HALO recruits from these mine-impacted communities so that local people have ownership of clearance. A large number of women work for HALO as deminers, clearance managers, finance clerks and data analysts, which was particularly inspiring. One particular minefield on the border with Thailand is located on a mountainside that requires a 40-minute hike up seemingly vertical slopes first thing in the morning. I was utterly humbled by the Cambodian men and women who charged up the mountain carrying all manner of demining equipment like detectors, stretchers, tool kits and more, without even breaking a sweat!

Communities are literally transformed after clearance in Cambodia as fields can be farmed, schools can be built, irrigation channels can be dug and health clinics regain access. HALO Cambodia’s men and women work incredibly hard and their determination to clear their country of mines and UXO is entirely tangible. The programme’s 27 years of experience has produced the best teachers for newcomers to mine action such as myself, and, for their patient guidance and expertise, I am very grateful.

Local people walking through land cleared by HALO, Somaliland

Somaliland

The self-declared independent state of Somaliland lies in northwest Somalia on the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden. Since declaring independence from British colonial rule in 1960, Somalilanders have sadly seen a lot of war – post-independence violence with southern Somalia, war with Ethiopia and a bitter civil war that began in the 1980s and continues in part to this day. In the face of immense challenges such as cities being razed to rubble, tens of thousands dead and natural disasters like drought, Somaliland confounded naysayers by re-asserting their independence and establishing a stable and relatively safe democratic society in 1991. Successful parliamentary and presidential elections have enabled some normality to take hold in Somaliland, yet the presence of mines and UXO as a deadly reminder of the turbulent past hampers development to this day.

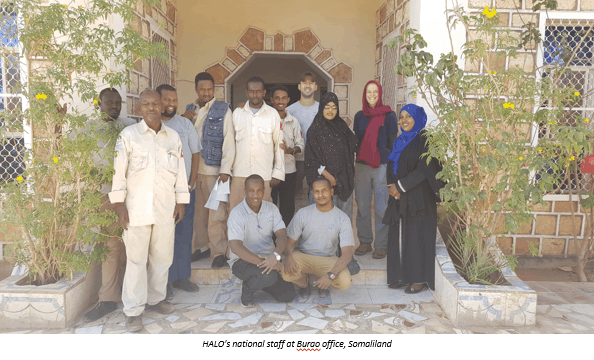

The welcome extended to any visitor by Somalilanders will be one of the warmest a person will ever experience – in my experience, they are proud and excited to display all that they have achieved in both mine clearance and nation building since the war ended. Many HALO Somaliland employees have impressive experience in academia and the military, bringing varied skills like engineering, mapping, book-keeping and explosive ordnance disposal to HALO. The finance manager in Somaliland HQ was a particularly amazing woman who took the time to share her personal story with me whilst I was there – fighting forced her family to move back and forth between north and south in search of safety, and each time they moved they left everything behind and rebuilt their lives from scratch. Poverty, the loss of family members and constant insecurity did not stop her from training to be a midwife whilst seeking refuge in neighbouring Ethiopia, and then obtaining a BA in accounting before finding HALO. She was graceful and assiduous.

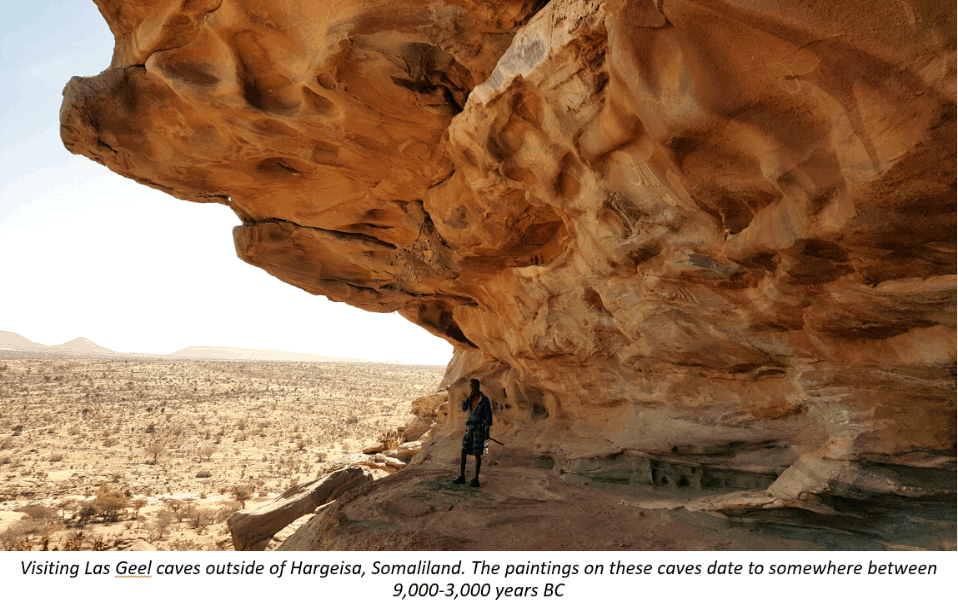

Mine clearance on roads and grazing lands will allow for continued development in Somaliland, securing livelihoods and improving future prospects for the next generation. Yet amidst the healing and development process, Somalilanders still know how to have fun. For example, we were taken swimming in the Gulf of Aden (no easy feat in a headscarf and modest clothing), introduced to deliciously rich coffee and North African reggae music in local restaurants, taken on a hike up to thousand-year-old cave paintings, introduced to the country’s beautiful exotic birds and treated to the finest display of stars as we camped out in demining camps.

When I told people I’d be going to Georgia and Abkhazia for phase two of my HALO operations training, the reaction was mostly –

“Georgia…as in the southern state in the USA?”

“Abkhazia, what is that?”

My scorn to those who don’t know Georgia and Abkhazia would flow faster and stronger now that I have visited these beautiful places. Georgia boasts a fascinating and rich culture, famous for its Orthodox Christian faith, rugby, pottery, snow-capped mountains, the ‘a guest is a gift from god’ mind-set, poetry, wrestling and much more. Perhaps most importantly (to my gluttonous self, at least!), Georgia is without doubt, the most fertile place I have ever been to – everything grows there in terms of fruits and vegetables. As such, it’s hardly surprising that Georgian cuisine is world-famous for being mind-bendingly delicious to the extent that neither words nor pictures can do it justice. My advice would be to go to Georgia as soon as possible and get stuck in to the feasting culture at a traditional banquet (N.B., wear trousers with some extra give). Banquets are also a great opportunity to experience the tradition of toasting, where delicious Georgian wine is drunk in honour of family, friends, future generations and national heroes who have given their lives for their homeland. Toasting culture is fundamentally a celebration of life and death, but it provides a stark reminder that Georgia’s history has been tumultuous; war, occupation, revolution and separation have all facilitated great human suffering in Georgia and a legacy of landmines and UXO. In particular, contamination in former military bases, international borders and agricultural land continues to hold back development and cause death and injury to civilians.

HALO van outside abandoned buildings, Abkhazia

Abkhazia, the partially recognised republic that declared independence from Georgia after a bitter conflict in the mid-1990s, was declared mine-impact free after 14 years of clearance operations by HALO. However, UXO remains a big problem in the region; widespread destruction during the war left buildings and infrastructure in tatters, and desperately needed regeneration is being held back by the presence of dangerous explosive items. The natural beauty of the region will no doubt attract many tourists in the future, but for now, continued funding for UXO clearance is essential to pave the way for construction, as well as reconciliation between previously warring ethnic factions. The experienced HALO staff in Georgia and Abkhazia shared their wealth of knowledge on munitions with me, and only with their help was I able to obtain my International Mine Action Standards Level 3 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Qualification.

Lucy working at a mountain minefield task in Samangan, Afghanistan

Afghanistan

As a visitor to Afghanistan, you are part of the family from the moment you arrive. Culture prescribes hospitality at the highest level, but the warmth of Afghan people feels far more genuine than something that is merely dictated by social norms. Every morning you take the time to greet colleagues and friends properly – asking about their family, their health and how their evening was. Local delicacies cooked by HALO staff are shared almost daily, and anything you might ever want will always be provided. It’s easy to feel at home here, and, in the relative security of Kabul, it’s also easy to forget that you’re in a country at war.

However, sadly Afghanistan is at war, and has been for many years. From the Soviet invasion in 1979 to the civil war throughout the 1990s, Taliban rule from 1996-2001 and persistent insurgency from 2001 onwards, fighting has been bitter and countrywide. The resulting mine and UXO contamination in Afghanistan varies from abandoned ammunition bunkers to Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs); from former battlefields littered with ordnance to minefields high up in the mountains.

Preparing items for demolition at the Central Demolition Site, Afghanistan

HALO Afghanistan is the largest of all HALO’s programmes, but also represents the largest mine clearance programme in the world. As of August 2018, there are over 3,700 staff working for HALO Afghanistan with only six of them non-Afghan (one of them being me). The programme’s managers who monitor mechanical clearance, fleet maintenance, operations, logistics, recruitment, training and more are almost entirely Afghan, combining both thirty years of experience in mine clearance and also backgrounds in the military, in teaching, in trade, in construction, in medicine and in academia. Sometimes when you are here in the ginormous HQ compound in Kabul, it feels like there is nothing HALO Afghanistan cannot do.

Since arriving in Afghanistan, national staff have taken me to see minefields in lofty mountain passes, flat desert areas, scenic picnic spots and rocky hillsides. They’ve introduced me to beneficiaries of clearance who graze their animals and cultivate their fields every day. They’ve taught me sentences in the local language, Dari, so that I might better communicate with people in day-to-day life. We’ve been extended invitations to weddings and BBQs. Whilst you never get used to hearing their horrific stories from war – family members killed, public beatings, years spent seeking refuge abroad, cultural destruction and lost opportunities, it’s also impossible to not feel inspired by their resolve, infectious sense of humour and vitality. Being posted to HALO Afghanistan as an international staff member is a compliment, a privilege and an amazing experience.

Landmines and ERW continue to present different threats to different people around the world – from aircraft bombs in Laos to unstable homemade mines in Sri Lanka; from border minefields in Myanmar to cluster munitions in Kosovo and minimum-metal mines in Angola that are extremely difficult to detect. Despite the creation of the International Convention on the Prohibition of the Use of Anti-Personnel Mines in 1997, landmines are still being laid which is a tragedy. Thanks to the dedication of HALO’s deminers and generous support from donors, lifesaving, peace building and poverty reducing clearance will continue in impacted communities around the world.

To find out more about the work of The HALO Trust, visit their website here. To get in touch with Experience Travel Group, please give us a call on 0207 924 7133 or head to our website.