Revisiting Burma after many years was very special for me. I was banned for more than twenty years and could not be sure I would be let in this time.

In 1988, when student protests against harsh military rule were beginning, I went to Burma on a tourist visa to report for the BBC. Journalists were not allowed in. I filed my reports only after I had left the country, but the reaction was immediate and very personal. The government newspaper published a full-page diatribe against me headed ‘An open letter to Nick Nugent of the BBC’.

It didn’t actually say what I had done wrong, but I knew. The BBC Burmese Service broadcast my reports back to the Burmese people. My ‘sin’ was to have told the Burmese people what was going on in their own country.

Those were dark days throughout Burma with regular blackouts demonstrating how far one of the region’s previously strong economies had sunk.

My return was special because it was happening at all. Burma – or Myanmar as we are encouraged to call it – is now ‘light’, a broadly happy country whose economy is gathering momentum after the lifting of western sanctions, though living standards have a long way to catch up with those of wealthy neighbours like Thailand and Malaysia.

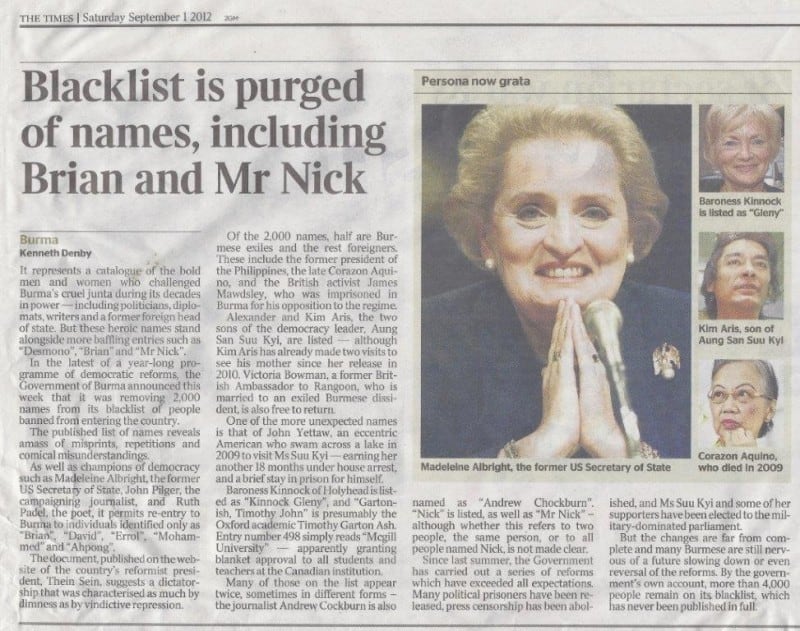

Since the ‘black’ list was abolished three years ago – something I learnt from a headline in the Times – I have been free to visit. The e-visa system was as easy as pie – done on-line with a positive result within hours – compared with the challenging process of old. Would they really let me back in?

When I arrived at Rangoon airport the youthfulness of the immigration officer made me realise she would have been in nappies when I committed my misdemeanour. Sure enough, I was barely scrutinised and with a quick stamp on my passport I was in. A Burmese doctor later complimented me saying: “What was once the black list is now regarded by the people as a golden list!”

Myanmar is a different place from the Burma I visited in the dark ages – and I don’t just mean the change of name, which may not seem natural to those reared on George Orwell’s ‘Burmese Days’ or with long enough memories to recall the wartime Burma Road and Railway.

Yet it has some logic about it. ‘Burmans’ are the majority in a country of numerous ethnic minorities – Karens, Kachins, Chin, Mon, Rakhine and Shan, for example. Calling the country ‘Myanmar’ embraces them all, not just the majority. The people of Myanmar have long called the country by that name and when said by a citizen ‘Myanmar’ sounds remarkably like ‘Burma’. However, you will not be misunderstood if you stick to the ‘old’ name.

Myanmar now welcomes tourists with open arms and provides the facilities to encourage them. There are multi-star hotels and resorts at all key destinations and comfortable means of transport to reach them. I can assure you that was not the case in the 1980s.

A main theme of any visit is pagodas, of which this devoutly Buddhist country has far more than its fair share, with crimson-robed monks in attendance. The pagodas are varied, and fascinating. Shwedagon Pagoda, 99 metres/325 feet high, dominates the skyline of Rangoon, the former capital now known as Yangon. It is said to contain eight strands of the Buddha’s hair.

Up-country, the most spectacular sight is the plain of some 4000 pagodas at Bagan. If you go in the dry season you can view them from a hot-air balloon, though I made a go of it on a fun but slow electronic bicycle! Bagan was denied UNESCO ‘World Heritage’ status because the military authorities built a road too close to the treasures. It deserves this accolade and will surely be awarded it one day – perhaps when they take the road up!

Next stop if you are doing the favoured tour will be the romantic sounding city of Mandalay, where the last Burmese King, Thibaw, resided in his palace in the late 18th Century until sent into exile by British colonisers. Amitav Ghosh tells a fictionalised version of the story in his epic novel ‘The Glass Palace’.

As for romance, that was all a misunderstanding caused by another famous writer. Rudyard Kipling was sailing back to Britain from India when his ship made a call at the southern city of Moulmein. There he fell for a Burmese beauty – ‘‘’er name was Supiyawlat, just like Thibaw’s queen” – inspiring his famous poem ‘Mandalay’. Kipling never visited Mandalay and the poem refers to “the road to Mandalay”, in reality the river Irrawaddy, Burma’s principal waterway. Nor did he ever meet his almond-skinned beauty again.

Regardless, Mandalay is definitely worth a visit to see ‘the world largest book’, Buddhist texts carved on stone tablets, and to climb Mandalay Hill for the spectacular view, though there is now a lift!

It’s a city you can cycle around if you are not intimidated by the traffic. Travellers keen to keep an eye or ear to the political mood should go to see the Vaudeville act by the ‘Moustache Brothers’, performed nightly in English, with their ‘take’ on the country’s military rulers.

Another fun thing to do from Mandalay is to take a comfortable and leisurely Irrawaddy cruise for which there are several different boats and itineraries. My choice would be to sail north to Katha, the town on which Orwell based ‘Burmese Days’, a fictional chronicle of British-ruled Burma.

Having reflected on how the generals have ruled Burma for nearly fifty years, it’s only fair that Orwell’s book reminds us how life in British-ruled Burma was not exactly a bed of roses either.

Most visitors stop at Inle Lake, famous for the way fishermen row their boats with one leg while standing and hauling in their fishing nets with the other. If you cannot quite picture this a visit is essential. There are other ways to spend your time, or you can just ‘chill out’, at this enchanting place in Myanmar’s exotic Shan State.

You could go and discover one of the previously lost complexes of pagodas emerging from the jungle. My ‘discovery’ was Kakku, some hours’ journey from Inle and well worth the effort.

Myanmar’s political system has yet to be fully reformed. The generals remain in charge till elections are due in November 2015. It is widely assumed that they will by voted out of office and that the party led by Nobel Peace Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi will take the most seats in parliament. ‘The Lady’, as she is widely known, is blocked from becoming president by virtue of her marriage to a foreigner, unless the constitution is amended.

The military appear to understand that their time is up and they will soon leave the stage. If they don’t, the sanctions imposed after they refused to accept a previous election, which Ms Suu Kyi’s party won, will be re-imposed.

However, repressive rule no longer stands in the way of tourism and famous Burmese hospitality has taken over. The country has transformed itself from darkness to light – and ‘black’ now means ‘golden’. Welcome to Myanmar, the ‘new’ Burma.

Experience Travel Group create personalised, distinctive and experience-based holidays in Myanmar. To see what’s possible, have a look here!